About 6 km east of Cusco, on Socorro Hill, lies our next destination - the archaeological complex of Q’enqo, located just 15 minutes from the city at an altitude of approximately 3,580 meters. The name Q’enqo comes from Quechua and means “labyrinth” or “zig-zag,” referring to the tunnels, passages, underground channels, or perhaps to the crooked canal carved into the rock above the ritual chamber. Q’enqo is one of the largest huacas (sacred places) in the Cusco region and served as an important Inca ceremonial and worship centre, where rituals in honour of the major gods were performed.

Około 6 km na wschód od Cusco, na wzgórzu Socorro, znajduje się nasz kolejny przystanek - kompleks archeologiczny Q’enqo. Położony jest zaledwie 15 minut jazdy od miasta, na wysokości około 3580 m n.p.m. Nazwa Q’enqo pochodzi z języka keczua i oznacza „labirynt” lub „zygzak”, nawiązując do sieci tuneli, przejść, podziemnych korytarzy albo do krętego kanału wykutego w skale przy komnacie rytualnej. Q’enqo należy do największych huacas, czyli świętych miejsc, w regionie Cusco i pełniło ważną funkcję ceremonialno-religijną w czasach Inków - to właśnie tutaj odbywały się rytuały ku czci najważniejszych bóstw.

Like many Inca huacas, Q’enqo was created from a naturally occurring rock formation and is entirely sculpted from living stone. Because of its strong religious significance, the site was largely destroyed during the Spanish colonial period. However, as it was carved directly into solid rock, parts of Q’enqo managed to withstand this destruction. What remains today are mainly the carved rock formations, while most of the original paths and aqueducts have disappeared. The complex consists of two main areas: Q’enqo Grande (also known as Hatun Q’enqo), the larger sector open to visitors, and Q’enqo Chico (Huchuy Q’enqo), a smaller area that is currently closed to the public.

Podobnie jak wiele innych inkaskich huacas, Q’enqo powstało na bazie naturalnej formacji skalnej i zostało w całości wykute w litej skale. Ze względu na swoje ogromne znaczenie religijne miejsce to zostało w dużej mierze zniszczone w okresie kolonizacji hiszpańskiej. Ponieważ jednak obiekty były bezpośrednio wykute w skale, część kompleksu zdołała przetrwać do naszych czasów. Obecnie zachowały się przede wszystkim rzeźbione formacje skalne, natomiast większość dawnych ścieżek i akweduktów uległa zniszczeniu. Kompleks składa się z dwóch głównych części: Q’enqo Grande (znanego również jako Hatun Q’enqo), czyli większego obszaru udostępnionego zwiedzającym, oraz Q’enqo Chico (Huchuy Q’enqo), mniejszej części, która pozostaje zamknięta dla publiczności.

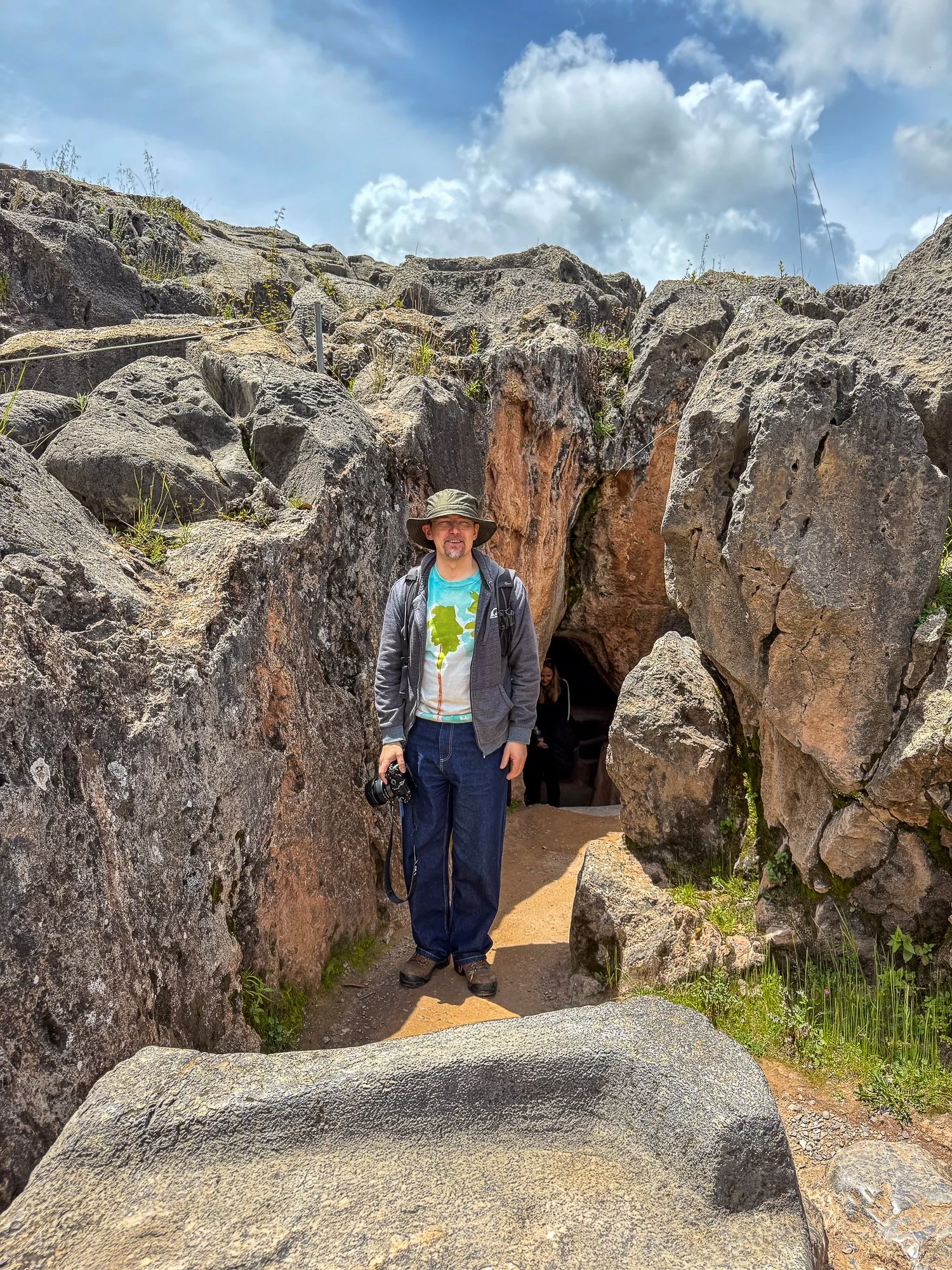

The most remarkable feature of Q’enqo is its underground Ritual Chamber, a single interconnected space carved entirely from a massive natural rock. The floor, ceiling, walls, ceremonial tables, niches, and tunnels were all sculpted from the same stone. Access is through a tunnel carved into the rock, alongside which runs a large zigzagging gutter. This channel leads into the main ritual area and is believed to have carried ceremonial chicha (a fermented corn beverage) or the blood of sacrificial animals. The discovery of numerous bones within the gutter suggests that this chamber was used for ritual sacrifices, most likely involving llamas and possibly humans.

This underground space also played a role in Inca death rituals. One niche may have been used to place mummies, while another reportedly held a large silver plate that reflected the sun’s rays into the chamber. Being underground, the Sacrifice Chamber symbolised an entrance to the world of the dead, and rituals may have taken place on a stone slab carved into the rock. Some researchers believe the tunnels were also used for the embalming or mummification of Inca nobles, although this interpretation is not universally accepted.

Najbardziej niezwykłym elementem Q’enqo jest podziemna Komnata Rytualna - pomieszczenie wykute w całości w potężnej, naturalnej skale. Podłoga, sufit, ściany, stoły ceremonialne, nisze oraz tunele zostały wyrzeźbione z tego samego bloku kamienia. Do wnętrza prowadzi tunel wykuty w skale, wzdłuż którego biegnie duży, zygzakowaty kanał. Prowadzi on do głównej przestrzeni rytualnej i prawdopodobnie służył do odprowadzania ceremonialnej chichy (fermentowanego napoju z kukurydzy) lub krwi zwierząt ofiarnych. Odkrycie licznych kości w tym kanale wskazuje, że komnata była miejscem rytualnych ofiar, najczęściej z lam, ale być może także z ludzi.

Podziemna przestrzeń pełniła również ważną rolę w inkaskich obrzędach związanych ze śmiercią. Jedna z nisz służyła prawdopodobnie do umieszczania mumii, natomiast w innej znajdowała się duża srebrna płyta, która odbijała promienie słoneczne i kierowała je do wnętrza komnaty. Ze względu na swoje położenie pod ziemią Komnata Rytualna symbolizowała wejście do świata zmarłych, a rytuały mogły odbywać się na kamiennej płycie wykutej w skale. Niektórzy badacze uważają również, że tunele wykorzystywano do balsamowania lub mumifikacji inkaskiej elity, choć interpretacja ta nie jest powszechnie akceptowana.

Above ground, Q’enqo shows clear evidence of structures related to Inca astronomy and cosmology. As with many Inca stoneworks, the carved shapes appear to represent stars and constellations. An Intihuatana, or “sun post,” or “the place where the sun is tied”can also be seen, and it may have been used to mark solar events.

Na powierzchni Q’enqo widać wyraźne ślady budowli związanych z astronomią i kosmologią Inków. Podobnie jak w wielu innych inkaskich kamiennych konstrukcjach, wyryte kształty zdają się przedstawiać gwiazdy i konstelacje. Znajduje się tu również Intihuatana, czyli „słup słoneczny” lub „miejsce, w którym wiąże się słońce”, który prawdopodobnie służył do obserwacji i wyznaczania ważnych wydarzeń słonecznych.

From Q’enqo, the Incas would have looked down upon the city of Cusco, which lay in the heart of the valley like the centre of the world. The elevated position of Socorro Hill gave them not only a commanding view of the urban centre but also a spiritual perspective: the city itself was part of a sacred landscape, intertwined with rivers, mountains, and huacas. From this vantage point, the Incas could observe the alignment of the sun and stars over the city, marking solstices, equinoxes, and other important celestial events that guided agricultural and ceremonial calendars.

Z Q’enqo Inkowie spoglądali w dół na miasto Cusco, położone w sercu doliny niczym centrum świata. Wysokie położenie wzgórza Socorro dawało im nie tylko panoramiczny widok na miasto, lecz także duchową perspektywę: samo Cusco było częścią świętego krajobrazu, splecionego z rzekami, górami i miejscami świętymi (huacas). Z tego punktu Inkowie mogli obserwować ustawienie słońca i gwiazd nad miastem, wyznaczając przesilenia, równonoce oraz inne ważne zjawiska astronomiczne, które regulowały kalendarze rolnicze i ceremonialne.

Surrounding the archaeological site is an eucalyptus forest filled with imposing trees, which has been declared a UNESCO World Heritage Site.

Wokół Q’enqo rośnie las eukaliptusowy, który został wpisany na listę światowego dziedzictwa UNESCO.